The last three years have presented extraordinarily complex challenges in higher education, as we navigated pivots and experienced ongoing disruptions in our teaching and learning spaces, environments, and communities. We became more aware of the systemic inequities that exist across our organizations. We’ve questioned and leaned into the opportunities and challenges our organizational infrastructure presents (e.g., our technologies, spaces, governance, decision-making, and planning). We’ve also worked to navigate challenges with our individual and collective well-being, anxiety, burnout and exhaustion. Throughout the pandemic, I heard strong leaders described by words such as: systems-level thinkers, networked, self-aware, mindful, equitable, inclusive, empathetic, compassionate, courageous, hopeful, and relational.

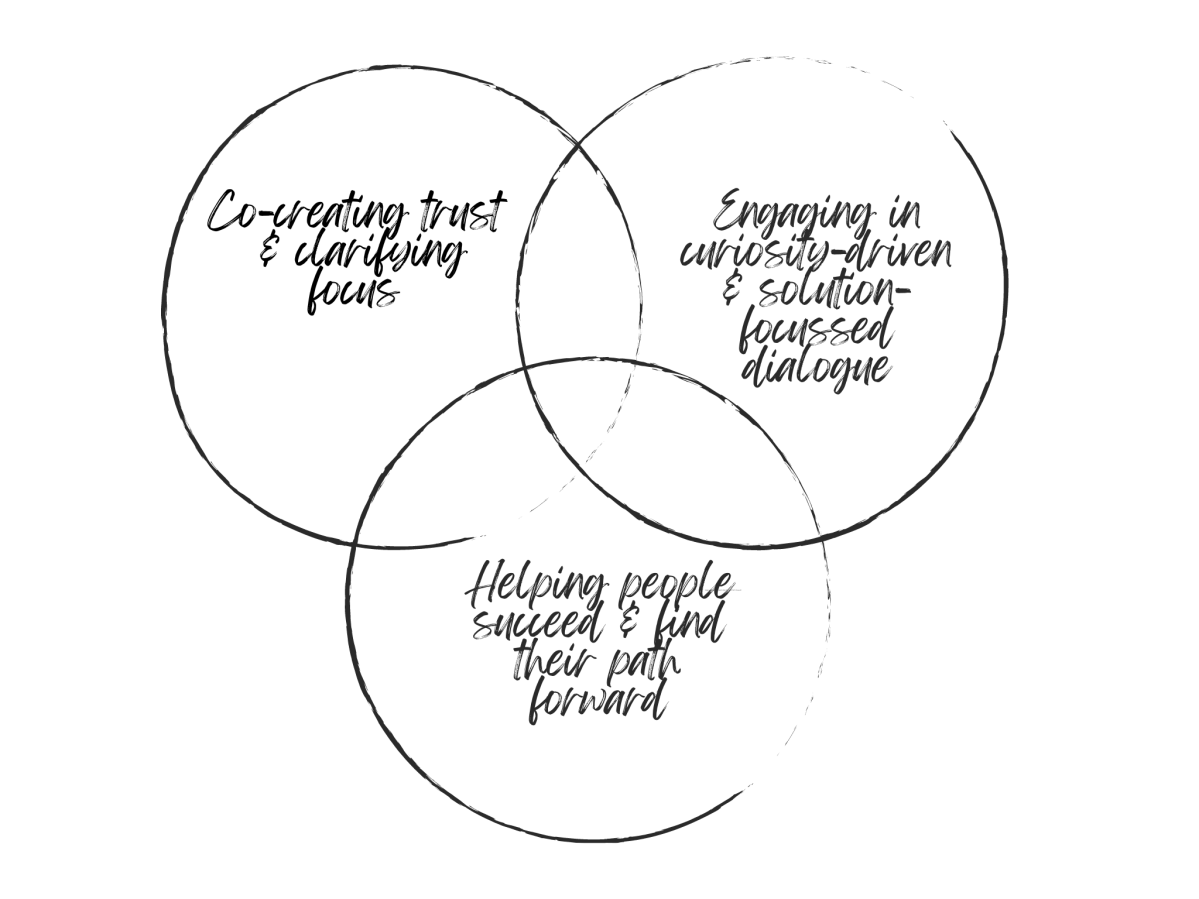

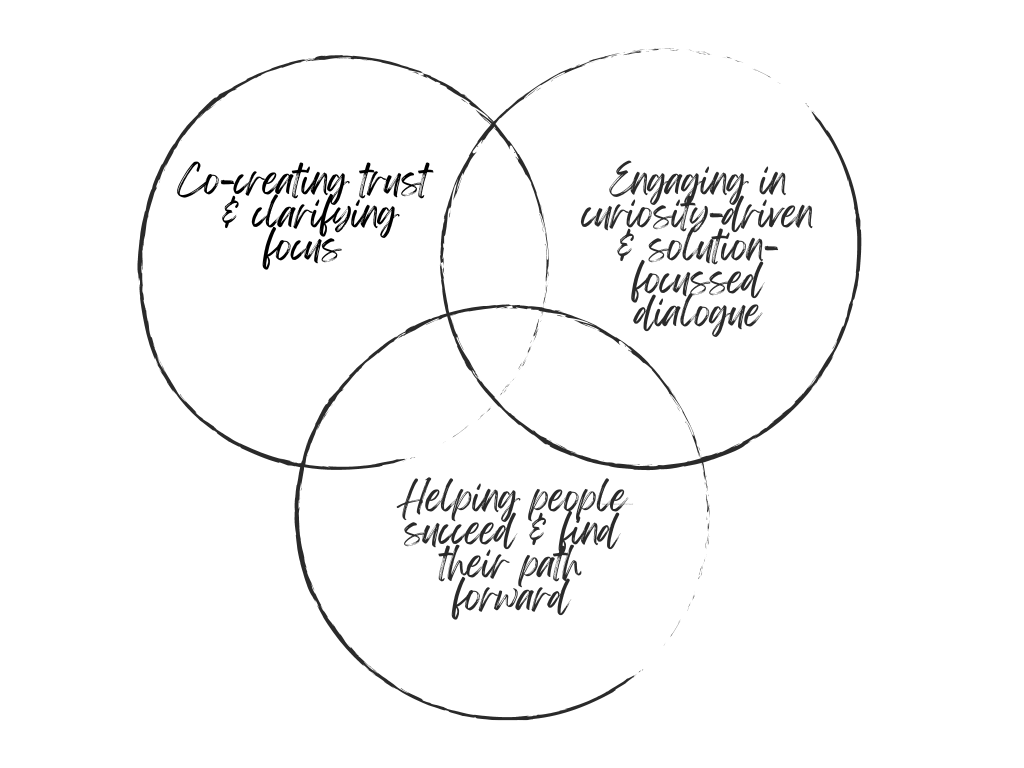

Perhaps we’ve experienced some foundational shifts in leadership practices, which will continue to carry us forward in higher education? I’ve conceptualized these shifts as three foundational leadership practices: 1) a leadership of compassion; 2) a leadership of connection; and 3) a leadership of hope.

A leadership of compassion

Throughout the pandemic we experienced challenges that were difficult to comprehend. We felt the anxiety, isolation, and overwhelming complexities of uncertainty. Building upon Worline and Dutton (2017), Waddington (2021) describes compassion as noticing and making meaning of suffering, feeling empathy for those experiencing suffering, and taking action to alleviate suffering. Throughout the pandemic, leaders across higher education demonstrated compassion by reaching out to their teams, checking in with their colleagues to see how they were doing, demonstrating empathy and vulnerability in the face of ongoing uncertainty, providing reassurance, embracing dialogue, listening deeply to those around them, and demonstrating support through relational action (e.g., Lawton-Misra and Pretorius, 2021). They asked about other’s feelings and well-being, and took action to alleviate barriers and reduce suffering where they could have influence. They suffered themselves. They made mistakes and experienced failure. They learned and unlearned. Their emotions fluctuated, and often, were relentlessly raw and challenging. It became harder to respond, rather than react in the face of ongoing challenge and uncertainty. They demonstrated resilience and vulnerability by sharing their experiences, connecting with peers, normalizing help-seeking, and cultivating a deeper sense of self-awareness, self-compassion, and mindfulness.

What does a leadership of compassion look like moving forward?

Hougaard et al. (2021) share practical strategies for demonstrating wise compassion through self-compassion, intention, transparency, and mindfulness. The Conscious Leadership Group’s Above the Line/Below the Line Framework is a fantastic tool for fostering ongoing self-awareness and reflection. Dr. Kristin Neff’s work on developing self-compassion through self-kindness, a recognition of common humanity and mindfulness is transformative.

A leadership of connection

There were no simple answers to the challenges we faced during the pandemic. Decision-making was forced by situations beyond our control and the need for action was accelerated at relentlessly unsustainable rates. There were no right answers. The disruptions were constant. The impacts of the pandemic were complex and disproportionately affected equity-deserving groups (Abdrasheva et al., 2022; Bassa, 2022; Jehi et al., 2021). Throughout the pandemic, many leaders embraced the power of shared leadership, relationships, and collaborative decision-making. They brought together informal and formal networks to surface and grapple with challenges, and to share knowledge across once-siloed institutional, faculty, departmental and unit-level boundaries. They identified and connected core networks of problem-solvers, instilled confidence, fostered trust, built relationships, facilitated consensus, listened deeply, and leveraged the strengths of local-level leaders, influencers, and change-catalysts (Bleich and Bowles, 2021; Bassa, 2022; Mehrotra, 2021). They looked across multiple organizational levels to influence systems-level awareness and change. They created peer, cross-institutional, national, and international networks of knowledge and resource sharing, breaking through past barriers of competition and scarcity. They leaned into the realities of the systemic and structural inequities that became increasingly visible across our university structures.

The work of fostering connection and developing relationships takes time and intentional effort. Research suggests that one of the most important factors associated with student confidence in their learning during the pandemic was their sense of connection with their peers and their professors (Guppy et al., 2022). This finding speaks volumes to the importance of developing and sustaining meaningful relationships bounded by belonging and connection across higher education.

How can we continue to foster connection moving forward?

We can continue to bring networks together to grapple with important teaching and learning issues. A few topics that continue to surface: student assessment, academic integrity, artificial intelligence, experiential and work-integrated learning, learning spaces and technologies, equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility, truth, reconciliation and Indigenous engagement, the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), mental health and well-being, student learning skills, engagement and metacognition, sustainability and climate change, blended and online learning, learning pathways, stackable and personalized learning, and micro-credentialing. We can listen deeply to one another – with an intention to understand and heal, rather than to respond, judge, debate, criticize, or problem solve. We can trust and provide resources and support to pedagogical catalysts, influencers and local educational leaders who care deeply about teaching and make an effort to develop local teaching and learning networks and communities (Myllykoski-Laine et al., 2022). We can create accessible spaces, events, and initiatives for open knowledge sharing about teaching and learning, within our academic units, institutions, nationally and globally. A fantastic exemplar is Dr. Maha Bali’s and colleagues’ work on Equity Unbound – an open, and freely available resource that is filled with strategies to inspire online community-building, through the principles of equity and care.

A leadership of hope

It was easy to feel overwhelmed and consumed during the pandemic. The challenges we faced felt enormous, and it was often difficult to see where and how we could have influence. We learned the importance of establishing a leadership of hope. It was a hope that acknowledged that what we were living through was challenging and hard. We were experiencing a world that had become increasingly uncertain, volatile, and unpredictable.

Despite the challenges and inequities which surround us, critical hope requires us to come together in community to connect in meaningful ways, to envision a better and more inclusive future, and to take incremental action to create positive change (Riddell, 2020). Critical hope is a “…hope that is neither naïve nor idealistic;” it is both critical and emotional, and it works to dismantle injustice and despair in our systems and structures (Grain & Lund, 2016, p.51). It accepts that through connection and collective action, we can help to reduce suffering and move towards healing.

During the pandemic, leaders sustained a sense of critical hope by naming and leaning into the systemic inequities that continued to emerge, by acknowledging the ongoing uncertainty and suffering that occurred, by creating a sense of purpose and meaning in the face of uncertainty, by demonstrating a continuous perseverance to take action, by maintaining honest communication, by accepting and moving beyond mistakes, by establishing open feedback channels, and by creating an organizational culture of continuous learning and growth (Beilstein et al., 2021; Bassa, 2022). Leaning into uncertainty, systemic inequities, failure and ongoing learning took courage. It was an intensely vulnerable time for leaders – many of whom drew focussed attention to the power of emotion and humanity to help us through it all.

How do we continue to move forward through a leadership of hope?

McGowan and Felten (2021) highlight that deep inequities persist in higher education. They present a wonderful equation for continued reflection that I believe provides a foundation for leading through hope (p. 474):

Agency

‘I can change in meaningful ways despite the systems and structures constraining me’

+

Pathways

‘I see specific and purposeful steps I can take’

=

Hope

When feeling overwhelmed, this framework provides me pause to stop and ask:

1) What is one meaningful change that I can contribute to despite the systems and structures that constrain me?

2) What are some specific and purposeful steps I can take to move towards that change?

3) Who/what are the support networks I can draw upon for support and accountability?

There is always something I can do to help move towards the positive changes we most aspire to in higher education.

I am curious how these three shifts in leadership (i.e., a leadership of compassion; a leadership of connection; a leadership of hope) resonate with you? What would you change or add? What shifts have you observed? What can we learn moving forward?

References

Abdrasheva, D. Escribens, M., Sazalieva, E., do Nascimento, D. V., & Yerovi, C. (2022). Resuming or reforming? Tracking the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education after two years of disruption. UNESCO. https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IESALC_COVID-19_Report_ENG.pdf

Beilstein et al. (2021) Leadership in a time of crisis: Lessons learned from a pandemic. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology 35 (2021) 405e414

Bassa, B. (2022). Leading Into a New Higher Education as It Emerges in the Present Moment. In International Perspectives on Leadership in Higher Education (Vol. 15, pp. 271-290). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Bleich, M. R., & Bowles, J. (2021). A model for holistic leadership in post-pandemic recovery. Nurse Leader, 19(5), 479-482.

Guppy, N., Matzat, U., Agapito, J., Archibald, A., De Jaeger, A., Heap, T., … & Bartolic, S. (2023). Student confidence in learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: what helped and what hindered?. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(4), 845-859.

Grain, K. M., & Lund, D. E. (2017). The social justice turn: Cultivating’critical hope’in an age of despair. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 23(1).

Jehi, T., Khan, R., Dos Santos, H., & Majzoub, N. (2022). Effect of COVID-19 outbreak on anxiety among students of higher education; A review of literature. Current Psychology, 1-15.

Lawton-Misra, N., & Pretorius, T. (2021). Leading with heart: academic leadership during the COVID-19 crisis. South African Journal of Psychology, 51(2), 205-214.

McGowan, S., & Felten, P. (2021). On the necessity of hope in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(4), 473-476.

Mehrotra, G. R. (2021). Centering a pedagogy of care in the pandemic. Qualitative Social Work, 20(1-2), 537-543.

Myllykoski-Laine, S., Postareff, L., Murtonen, M., & Vilppu, H. (2022). Building a framework of a supportive pedagogical culture for teaching and pedagogical development in higher education. Higher Education, 1-19.

Riddell, J. (2020) Combatting toxic positivity with critical hope. University Affairs. https://www.universityaffairs.ca/opinion/adventures-in-academe/combatting-toxic-positivity-with-critical-hope/

Worline, M. C. & Dutton, J. E. (2017). Awakening compassion at work: The quiet power that elevates people and organizations. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler

Waddington, K. (2021). Introduction: Why compassion? why now?. In Towards the Compassionate University (pp. 5-22). Routledge.